Time Out of Mind

| Time Out of Mind | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Studio album by Bob Dylan | ||||

| Released | September 30, 1997 | |||

| Recorded | 1996-1997 | |||

| Genre | Blues rock, rock, country blues | |||

| Length | 72:50 | |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Producer | Daniel Lanois | |||

| Professional reviews | ||||

|

||||

| Bob Dylan chronology | ||||

|

||||

Time Out of Mind is the thirtieth studio album by American singer-songwriter Bob Dylan, released in September 1997 on Columbia Records. It is his first double studio album as it was released on vinyl since 1970´s Self Portrait. (It was released also as a single CD).

For fans and critics, the album marked Dylan's artistic comeback after he struggled with his musical identity throughout the 1980s, and hadn't released any original material since Under the Red Sky in 1990. Time Out of Mind is hailed as one of the singer-songwriter's best albums, and it went on to win three Grammy awards, including Album of the Year in 1998. It also made Uncut magazine's Album of the Year. Furthermore, the album is ranked #408 on Rolling Stone's list of The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time in 2003.[1]

The album features a particularly atmospheric sound, the work of producer (and past Dylan collaborator) Daniel Lanois, whose innovative work with carefully placed microphones and strategic mixing was detailed by Dylan in the first volume of his memoirs, Chronicles: Volume One. Despite being generally complimentary to Lanois, especially his work on the 1989 album Oh Mercy, Dylan has voiced dissatisfaction with the sound on Time Out of Mind. He has gone on to self-produce his subsequent albums.

Contents |

Further details

Shortly after completing the album, Dylan became seriously ill with near-fatal histoplasmosis.[2] His forthcoming tour was canceled, and Dylan spent most of June 1997 in excruciating pain.

Time Out of Mind's revitalization of Dylan's career extended all the way to the Grammys where it won multiple awards, including "Album of the Year" in early 1998. It was also voted as the best album of the year in The Village Voice Pazz & Jop critics poll. With all the media attention and praise, U.S. sales soon passed platinum, a feat that a Bob Dylan album had not reached in nearly two decades.

Recording sessions

In April 1991, Dylan told Paul Zollo that "there was a time when the songs would come three or four at the same time, but those days are long gone...Once in a while, the odd song will come to me like a bulldog at the garden gate and demand to be written. But most of them are rejected out of my mind right away. You get caught up in wondering if anyone really needs to hear it. Maybe a person gets to the point where they have written enough songs. Let someone else write them."

Dylan's last album of original material had been 1990's Under the Red Sky, a critical and commercial disappointment. Not so to his devoted fans, that heard a sympathetic Dylan to a troubled world shake it´s webs to start anew, at the same time of the release of the Traveling Wilburys Vol. 3. Robert Christgau of The Village Voice, who wrote, "To my astonishment, I think Under the Red Sky is Dylan's best album in 15 years, a record that may even signal a ridiculously belated if not totally meaningless return to form...It's fabulistic, biblical...the tempos are postpunk like it oughta be, with [Kenny] Aronoff's sprints and shuffles grooving ahead like '60s folk-rock never did." And Paul Nelson, writing for Musician, called the album "a deliberately throwaway masterpiece." When the Voice held its Pazz & Jop Critics Poll for 1990, Under the Red Sky placed at #39. Since then, he has released two albums of folk covers and a live album of older compositions; there had been no signs of any fresh compositions until 1996.

Dylan even demoed some of the songs in the studio, something he rarely did. According to drummer Winston Watson, elements of Dylan's touring band (including Watson himself) were involved in these sessions. Dylan also used these loose, informal sessions to experiment with new ideas and arrangements. At one point during the sessions, Dylan improvised a country-blues riff of indeterminate origin which was later sampled as the backing track for "Dirt Road Blues." ("He made me pull out the original cassette, sample sixteen bars and we all played over that [for the released version]," recalls Daniel Lanois.) "Can't Wait" and "Not Dark Yet" were also recorded at these early sessions, with "Not Dark Yet" featuring "a radically different feel," according to Lanois. "[The demo of 'Not Dark Yet'] was quicker and more stripped-down and [later during the formal studio sessions], he changed it into a civil war ballad."[3]

In a televised interview with Charlie Rose, Lanois recalled Dylan talking "about spending a lot of late nights working on this chapter of work. And, when he finished the words, he believed that the record is done, the record was written. He said, 'you know, we can do a waltz version, we can do this in 4/4, it can be up, it can be down, it can be these kind of chords, you know whatever we decide to do with it, that's that.' But what's important is that it's written."

Dylan continued rewriting lyrics until January 1997, when the official album sessions began. It would mark the second collaboration between Dylan and his chosen producer, Daniel Lanois, who had previously produced Dylan's 1989 release, Oh Mercy. Lanois had just finished producing Emmylou Harris's Wrecking Ball when Dylan asked him to produce the sessions for Time Out of Mind. According to Lanois, "What we...did this time was make reference to some old records from the 1950s that Bob really likes because they had a natural depth of field which was not the result of a mixing technique. You get the sense that somebody is in the front singing, a couple of other people are further behind and somebody else is way in the back of the room. So we set up the studio like that."

"The recording process is very difficult for me," Dylan conceded. "I lose my inspiration in the studio real easy, and it's very difficult for me to think that I'm going to eclipse anything I've ever done before. I get bored easily, and my mission, which starts out wide, becomes very dim after a few failed takes and this and that."

By now, new personnel were hired for the album, including slide guitarist Cindy Cashdollar and drummers Jim Keltner and Brian Blade. Both Cashdollar and Blade were hired by Lanois while Dylan brought in Keltner, who had previously toured with Dylan in 1979. Dylan also hired Nashville guitarist Bob Britt, Duke Robillard, organist Augie Meyers, and Jim Dickinson to play at the sessions.

With two different sets of players competing in performance and two producers with conflicting views on how to approach each song, the sessions were far from disciplined. Years later, when asked about Time Out of Mind, Dickinson replied, "I haven't been able to tell what's actually happening. I know they were listening to playbacks, I don't know whether they were trying to mix it or not! [Laughs] Twelve musicians playing live - three sets of drums, [Whistles] it was unbelievable - two pedal steels, I've never even heard two pedal steels played at the same time before! It was, like, sheer chaos for an hour and a half and then eight to ten minutes of beautiful music. The playbacks were chaos, when Dylan comes to mix it I think he's gonna be in a lot of trouble. I don't know man, I thought that much was overdoing it, quite frankly. I'm a big fan and you never know what a masterful producer can do - producing is quite a subversive activity - so I can't really make any judgements until I hear the mixes. All I was doing was playing piano, Augie Meyers (Sir Douglas Quintet) was playing organ."

Dickinson does admit that "During (those eight to ten minutes) we'd nail it to the wall. [But Dylan] doesn't want it nailed down too tight. He definitely wants it loose...If we got too close to 'arrangements,' he would change the tempo and the key radically."

"In the past, when my records were made, the producer, or whoever was in charge of my sessions, felt it was just enough to have me sing an original song," said Dylan. "There was never enough work put into developing the orchestration, and that always made me feel very disillusioned about recording. Time Out of Mind is more illuminated, rather than just a song and the singing of that song. The arrangements or structures are really an integral part of the whole."

Lanois admitted some difficulty in producing Dylan. "Well, you just never know what you're going to get. He's an eccentric man, and you might get something great on the first take, or [chuckling] you may get nothing at all. You know, I mean, what we would do, Bob and I would go out to the parking lot and speak in the absence of the band. The band would wait in the studio. We'd go out in the parking lot and speak and make a plan for the next song."

In a later interview, Lanois elaborated, saying "Bob and I...would step out into the parking lot, because he would never discuss anything openly in front of the band, in terms of intimate details of the songs," recalled Lanois. "Like the song 'Standing in the doorway.' We were in the parking lot and I said 'listen, I love "Sad-eyed lady of the lowlands". Can we steal that feel for this song?' And he'd say 'you think that'd work?' Then we'd sit on the fender of a truck, in this parking lot in Miami, and I'd often think, if people see this they won't believe it! Me and Bob Dylan just sitting here, strumming guitars, working out chords for a session!"[3] In another interview, Lanois recalls the same anecdote with some different details: "In regard to last minute musical decisions, I remember saying to Bob, "You know, Bob, one of my favorite songs of yours is 'Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.' It's in a kind of 6/4. I said, 'It would be great to have something that feels that way on the record. Is there one of the songs that might lend itself to that time signature?' And he said, 'Well, this one 'Standing in the Doorway Crying' [sic], let's try that.'"

Asked why Dylan did not "discuss anything" in front of musicians, Lanois responded, "Well, he doesn't like too much democracy...He respects my commitment, knows I love him and want the best for him. He also knows he can't bulldoze me too hard; I'll put up a fight. So it's a two-way street."[3]

In subsequent interviews, Dylan cited Buddy Holly as an influence during the recording sessions. "You know, I don't really recall exactly what I said about Buddy Holly," said Dylan, "but while we were recording, every place I turned there was Buddy Holly. You know what I mean? It was one of those things. Every place you turned. You walked down a hallway and you heard Buddy Holly records like 'That'll Be the Day.' Then you'd get in the car to go over to the studio and 'Rave On' would be playing. Then you'd walk into this studio and someone's playing a cassette of 'It's So Easy.' And this would happen day after day after day. Phrases of Buddy Holly songs would just come out of nowhere. It was spooky. [laughs] But after we recorded and left, you know, it stayed in our minds. Well, Buddy Holly's spirit must have been someplace, hastening this record." Dylan would remember Holly when Time Out of Mind won the Grammy for Album of the Year; during his acceptance speech, Dylan said, "I just wanted to say, one time when I was about sixteen or seventeen years old, I went to see Buddy Holly play at the Duluth National Guard Armory [one evening in late January of 1959]...I was three feet away from him...and he looked at me. And I just have some sort of feeling that he was -I don't know how or why- but I know he was with us all the time we were making this record in some kind of way."

With Time Out of Mind, Lanois "produced perhaps the most artificial-sounding album in [Dylan]'s canon," says author Clinton Heylin, who described the album as sounding "like a Lanois CV."[4] In a March 1999 interview in Guitar World Magazine, Dylan discussed the sound of Time Out of Mind in relation to past works like Highway 61 Revisited, Blood on the Tracks, and Infidels:

"Those records were made a long time ago, and you know, truthfully, records that were made in that day and age all were good. They all had some magic to them because the technology didn't go beyond what the artist was doing. It was a lot easier to get excellence back in those days on a record than it is now. I made records back then just like a lot of other people who were my age, and we all made good records. Those records seem to cast a long shadow. But how much of it is the technology and how much of it is the talent and influence, I really don't know. I know you can't make records that sound that way any more. The high priority is technology now. It's not the artist or the art. It's the technology that is coming through. That's what makes Time Out of Mind... it doesn't take itself seriously, but then again, the sound is very significant to that record. If that record was made more haphazardly, it wouldn't have sounded that way. It wouldn't have had the impact that it did. The guys that helped me make it went out of their way to make a record that sounds like a record played on a record player. There wasn't any wasted effort on Time Out of Mind, and I don't think there will be on any more of my records."

The songs

A few critics, including NPR's Tim Riley, drew parallels between the album's title and the Steely Dan song of the same name (first issued on their 1980 album, Gaucho) , but the phrase goes back at least to 1596 when Shakespeare used it in Mercutio's Queen Mab speech in Act 1.4 of Romeo and Juliet.

In a 1997 interview, Dylan said that the songs on Time Out of Mind "naturally hung together because they share a certain skepticism. They're more concerned with the dread realities of life than the bright and rosy idealism popular today."

In an article published in The Chicago Tribune on September 28, 1997, Greg Kot writes, "Dylan projects the unease of someone adrift in a world that he ceases to understand, and that ceases to understand him. Yet he finds a strange comfort in his surroundings. 'You could say I'm on anything but a roll,' he sings [on 'Highlands'], one of many instances of the album's gallows humor. The music, anchored by Dylan contemporaries such as pianist Jim Dickinson and organist Augie Myers, hovers like an eerie David Lynch soundtrack and echoes the solo-free groove and grind of Dylan's '60s masterpieces. With Lanois' painterly production giving the songs a three-dimensional depth, the arrangements frame Dylan's voice as few recent recordings have.

"Dylan does not push his voice beyond its limits, but rather sing-speaks barely above a hush, as though holding an imaginary conversation with a distant lover, perhaps even his long-departed audience. He sings about love gone cold, but until the epic closing song, 'Highlands,' that loss never acquires a human face. In this 16+ minute epic, the singer briefly recaptures the conversational, playful and erotically charged tone of his youth.

"If the Dylan of World Gone Wrong echoed Flannery O'Connor, the Dylan of Time Out of Mind evokes playwright Samuel Beckett and his spare, unsentimental poetry of despair. He is confident of only one thing: 'When you think you've lost everything, you find out you can always lose a little more.' ['Trying to Get To Heaven']

"Not Dark Yet" is arguably the most celebrated song on Time Out of Mind, and is perhaps the clearest example of John Keats' influence on Dylan's writing; it is even possible that "Not Dark Yet" was grown out of Keats' own work. In his book, Dylan's Visions of Sin, Christopher Ricks, a Boston University professor of humanities, draws parallels between "Not Dark Yet" and the Keats poem Ode to a Nightingale. Broken down line for line, "similar turns of phrase, figures of speech, [and] felicities of rhyming" can be found throughout "Not Dark Yet" and the Ode. Ricks also argues that "there is a strong affinity with Keats in the way that in the song night colours, darkens, the whole atmosphere while never being spoken of," just as Keats used winter to color and darken the atmosphere in another poem he wrote, To Autumn. "Dylan's refrain or burden is 'It's not dark yet, but it's getting there.' He bears it and bares it beautifully, with exquisite precision of voice, dry humour, and resilience, all these in the cause of fortitude at life's going to be brought to an end by death."[5] Dylanologist AJ Weberman looked at this poem as being the result of illness: “I was born here and I'll die here against my will” no matter how bad things get I am going to fight it out and not take my own life “I know it looks like I'm moving” I know it looks like I’m healthy since I perform frequently all over the world “but I'm standing still” but I am a walking dead man “Every nerve in my body is so vacant and numb” I have been over-medicated to the point where any nerve that might cause pain has been neutralized “I can't even remember what it was I came here to get away from” and I wonder if this is worse than the actual symptoms of the disease? “Don't even hear a murmur of a prayer” I don’t have a prayer of getting rid of this disease Also “murmur” an abnormal sound of the heart “It's not dark yet, but it's getting there” I’m not dead yet but I am getting there.[6]

The longest composition ever recorded by Dylan, the 16-minute "Highlands" took its central motif ("My heart's in the highlands,") from a poem by Robert Burns called "My heart's in the highlands." Jim Dickinson later recalled Dylan "leaning over the equipment case working on the lyrics...with a pencil."

The song "Make You Feel My Love" was recorded twice under the title "To Make You Feel My Love" by two other popular artists. Billy Joel recorded the song for his Greatest Hits Volume III collection. Garth Brooks recorded the song as well for the Hope Floats soundtrack and then later released on Fresh Horses and The Ultimate Hits.

Outtakes

Seventeen known songs were recorded for Time Out of Mind, of which eleven would make the final cut. The first four that did not were "Mississippi", which was re-recorded for "Love and Theft", "No Turning Back", the Elizabeth Cotten composition "Shake Sugaree" and, according to Jim Dickinson "the best song there was from the session", "Girl from the Red River Shore". Two more songs, since released on The Bootleg Series Vol. 8 – Tell Tale Signs: Rare and Unreleased 1989–2006, were unveiled for the first time. "Dreamin' of You", released first as a free download on Dylan's website, had lyrics there were largely adapted into "Standing in the Doorway", though the melody and music are completely different. "Marching to the City" shares some of the same lyrics with "'Till I Fell In Love With You".

On past albums, some fans have criticized Dylan for some of the creative decisions made with his albums, particularly with song selection. Time Out of Mind was no different except this time the criticism came from colleagues who were disappointed to see their personal favorites left on the shelf. When Dylan accepted the Grammy Award for Album of the Year, he mentioned Columbia Records chairman Don Ienner, who "convinced me to put [the album] out, although his favorite songs aren't on it."

Unlike past sessions, none of these outtakes have circulated among collectors, something unprecedented for a Bob Dylan album. "With all of my records, there’s an abundance of material left over - stuff that, for a variety of reasons, doesn’t make the final cut. And other people seem to think they have some kind of right to it. That it’s their property even, which is baffling to me. I mean, you don’t drive a car out of the showroom without paying for it, do you? You don’t leave the supermarket without passing through the check-out with your goods. It's called stealing. Why the principle should be thought to be any different when it comes to music, I really don’t know."

According to Dylan, "If you had heard the original recording [of "Mississippi"], you'd see in a second" why it was omitted and recut for Love and Theft. "The song was pretty much laid out intact melodically, lyrically and structurally, but Lanois didn't see it. Thought it was pedestrian. Took it down the Afro-polyrhythm route - multirhythm drumming, that sort of thing. Polyrhythm has its place, but it doesn't work for knifelike lyrics trying to convey majesty and heroism.

"Maybe we had worked too hard on other things, I can't remember," Dylan continues, "but Lanois can get passionate about what he feels to be true. He's not above smashing guitars. I never cared about that unless it was one of mine. Things got contentious once in the parking lot. He tried to convince me that the song had to be 'sexy, sexy and more sexy.' I know about sexy, too. He reminded me of Sam Phillips, who had once said the same thing to John Prine about a song, but the circumstances were not similar. I tried to explain that the song had more to do with the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights than witch doctors, and just couldn't be thought of as some kind of ideological voodoo thing. But he had his own way of looking at things, and in the end I had to reject this because I thought too highly of the expressive meaning behind the lyrics to bury them in some steamy cauldron of drum theory. On the performance you're hearing, the bass is playing a triplet beat, and that adds up to all the multirhythm you need, even in a slow-tempo song. I think Lanois is an excellent producer, though."

Aftermath

Before the album was officially released, Dylan suffered a serious heart infection called pericarditis. A potentially serious condition (caused by the fungal infection histoplasma capsulatum), it makes breathing very difficult. "It was something called histoplasmosis that came from just accidentally inhaling a bunch of stuff that was out on one of the rivers by where I live," said Dylan. "Maybe one month, or two to three days out of the year, the banks around the river get all mucky, and then the wind blows and a bunch of swirling mess is in the air. I happened to inhale a bunch of that. That's what made me sick. It went into my heart area, but it wasn't anything really attacking my heart."

"Bob was starting to get a little sick when we were sequencing the album," recalled Lanois. "We had finished the record but then, at that point, what hit him was fluid around the heart and it probably had been building up for a while."

Following Dylan's May 1997 health scare, a number of columnists speculated that the songs on Time Out of Mind were inspired by an increased awareness of his own mortality. This, of course, was despite the fact that all of the songs were completed, recorded, and even mixed before he was hospitalized. Some critics like the Village Voice's Robert Christgau tried to tame such speculations, with Christgau writing "I'm convinced that Time Out of Mind is in no intrinsic way 'about death'...[What] the mortality admirers hear in it is their own...The timelessness people hear in it...what Dylan has long aimed for - simple songs inhabited with an assurance that makes them seem classic rather than received." A.J. Weberman, interviewed in Rolling Stone, believed the songs were the result of HIV that precedes AIDS [7]

In interviews following its release, Dylan, for the most part, downplayed these speculations with much reserve. However, he did give a blunt assessment in a 2001 interview published in The Times Magazine: "Where? Show me...I don’t see it like that. But again, that’s the story of my life...From 'The Times They Are A-Changin' onwards, people have misconstrued my words. They’ve attached the wrong meanings to them. That’s the status quo. That’s what happens, and there’s nothing to be done about it."

In the same interview, Dylan re-assessed Time Out of Mind, admitting some dissatisfaction with the results. "My recollection of [Time Out of Mind] is that it was a struggle. A struggle every inch of the way. Ask Daniel Lanois, who was trying to produce the songs. Ask anyone involved in it. They all would say the same. I trust the touring band I had at the time to do a good job in the studio, and so I hired these outside guys. But with me not knowing them, and them not knowing the music, things kept on taking unexpected turns. Repeatedly, I’d find myself compromising on this to get to that. As a result, though it held together as a collection of songs, that album sounds to me a little off...There’s a sense of some wheels going this way, some wheels going that, but hey, we’re just about getting there...But that’s my truthful memory of it, and that memory overshadows any gratification about its acceptance."

In 1999, Guitar World magazine had asked Dylan if Time Out of Mind would have made a satisfactory final release: "No, I don't think so. I think we are just starting to get my sound on disc, and I think there's plenty more to do. We just opened up that door at that particular time, and in the passage of time we'll go back in and extend that. But I didn't feel like it was an ending to anything. I thought it was more the beginning."

In 2003, the album was ranked number 408 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.[1]

Track listing

All songs were written by Bob Dylan.

- "Love Sick" – 5:21

- "Dirt Road Blues" – 3:36

- "Standing in the Doorway" – 7:43

- "Million Miles" – 5:52

- "Tryin' to Get to Heaven" – 5:21

- "'Til I Fell in Love with You" – 5:17

- "Not Dark Yet" – 6:29

- "Cold Irons Bound" – 7:15

- "Make You Feel My Love" – 3:32

- "Can't Wait" – 5:47

- "Highlands" – 16:31

Samples

Personnel

- Bob Dylan – guitar, harmonica, piano, vocals, producer

- Bucky Baxter – acoustic guitar, pedal steel (3,5,7,8)

- Brian Blade – drums (1,3,4,6,7,10)

- Robert Britt – Martin acoustic, Fender Stratocaster (3,6,7,8)

- Chris Carrol – assistant engineer

- Cindy Cashdollar – slide guitar (3,5,7)

- Jim Dickinson – keyboards, Wurlitzer electric piano, pump organ (1,2,4,5,6,7,10,11)

- Geoff Gans – art direction

- Tony Garnier – electric bass, acoustic upright bass

- Joe Gastwirt – mastering engineer

- Mark Howard – engineer

- Jim Keltner – drums (1,3,4,5,6,7,10)

- David Kemper – drums on "Cold Irons Bound"

- Daniel Lanois – guitar, mando-guitar, Firebird, Martin 0018, Gretsch gold top, rhythm, lead, producer, photography

- Tony Mangurian – percussion (3,4,10,11)

- Augie Meyers – Vox organ combo, Hammond B3 organ, accordion

- Susie Q. – photography

- James Wright - Wardrobe

- Duke Robillard – guitar, electric l5 Gibson (4,5,10)

- Mark Seliger – photography

- Winston Watson – drums on "Dirt Road Blues"

Title

The phrase "Time Out of Mind" is a synonym for "time beyond memory", or "time immemorial". The Oxford English Dictionary gives quotations for the phrase dating back to 1480, and variants as early as 1407. It is used in this context very near the start of Charles Dickens's novel Bleak House.

The album title might be a reference to a speech by Mercutio in Shakespeare's Romeo & Juliet (Act 1, Scene 4), but it dates back earlier than this-

Her chariot is an empty hazel-nut

Made by the joiner squirrel or old grub,

Time out o' mind the fairies' coachmakers.

And in this state she gallops night by night

Through lovers' brains, and then they dream of love;

The phrase is also used in some translations of the ancient Greek tragedy The Heracleidae by Euripides, first performed c. 430 BCE, in the Choral song in lines 608-617:

Luck pirouettes, and people who

Had conquered stoop, while drudges make

Their fortunes overnight. But you

Cannot get out of it or break

through by chicanery. You'll find

To try's a waste, time out of mind.[8]

It is included in the "Act of Submission" of the Narragansett Indians from 1644-

Nor can we yield over ourselves unto any, that are subjects themselves in any case; having ourselves been the chief Sachems, or Princes successively, of the country, time out of mind; and for our present and lawfull enacting herof, being so farre remote from His Majestie, wee have, by joynt consent, made choice of foure of his loyall and loving subjects, our trusty and well-beloved friends...

(The World Turned Upside Down, Calloway 1994)

It is also quoted in Greenblatt's Invisible Bullets from Thomas Harriot's account of Algonquian Indians:

The disease was so strange, that they neither knew what it was, nor how to cure it; the like by report of the oldest man in the country never happened before, time out of mind

(Invisible Bullets, Greenblatt)

It is also mentioned in Part Two of Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels and the title of a novel by Richard Cowper.

"Time out of mind" is also featured in Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass, in the poem "Song of the Broad-Axe": 'Served those who, time out of mind, made on the granite walls rough sketches of the sun, moon, stars, ships, ocean-waves'.

It is also in W.B Yeats's 1899 poem 'He Thinks of his Past Greatness...', in the lines: 'I have been a hazel-tree, and they hung / The Pilot Star and the Crooked Plough / Among my leaves in times out of mind'; and in his 1910 poem 'Upon a House shaken by the Land Agitation', in the lines: 'How should the world be luckier if this house, / Where passion and precision have been one / Time out of mind, became too ruinous/ To breed the lidless eye that loves the sun?'

Edna St. Vincent Millay also utilizes the phrase in her poem, 'Dirge Without Music: "So it is, and so it will be, for so it has been, time out of mind".

Another strong contender for inspiring the title of the album is Warren Zevon's song "Accidentally Like A Martyr", which is coincidentally heavily influenced by Dylan as its title suggests. The phrase is featured in the last line of the second verse. Furthermore, when it was revealed in 2002 that Zevon was dying from cancer, Dylan added for weeks in his concert setlists songs by Zevon. "Accidentally Like A Martyr" was the second most performed song, with 22 performances during October and November.

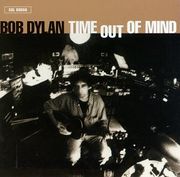

Album Cover

Behind the recording console, between the head of Dylan and the upper light, one can recognize an evanescent figure much resembling Allen Ginsberg. The "ghost of Allen" is perhaps a way to remember his friend who died a few months before the release of the disc. It can also be recognized a head resembling a young Dylan seemingly resting on the console with a top hat. Ginsberg was photographed in the past with a stars and stripes top hat.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "#408 Time Out of Mind" "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time" November 1, 2003. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- ↑ Weber, Bruce (May 29, 1997). " "Dylan in Hospital With Chest Pains; Europe Tour Is Off". The New York Times. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F50615F9395E0C7A8EDDAC0894DF494D81&scp=1&sq=dylan%20histoplasmosis&st=cse". Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Jackson, Joe (1997). "Ruminations on Mortality". In Thomson, Elizabeth and Gutman, David (2001), The Dylan Companion, pp. 306-09. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80968-0.

- ↑ Heylin, Clinton (2001). Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, p. 699. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-052569-X.

- ↑ Ricks, Christopher B. (2004). Dylan's Visions of Sin, p. 369. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-059923-5.

- ↑ Weberman, Alan Jules (2009) Rightwing Bob p298 Yippie Museum Press ISBN 1439256152

- ↑ http://www.rollingstone.com/news/story/5932153/tangled_up_in_bob/print

- ↑ Euripides, The Heracleidae. Euripides I. Translated by Ralph Gladstone. Edited by David Grene and Richmond Lattimore. (1955)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||